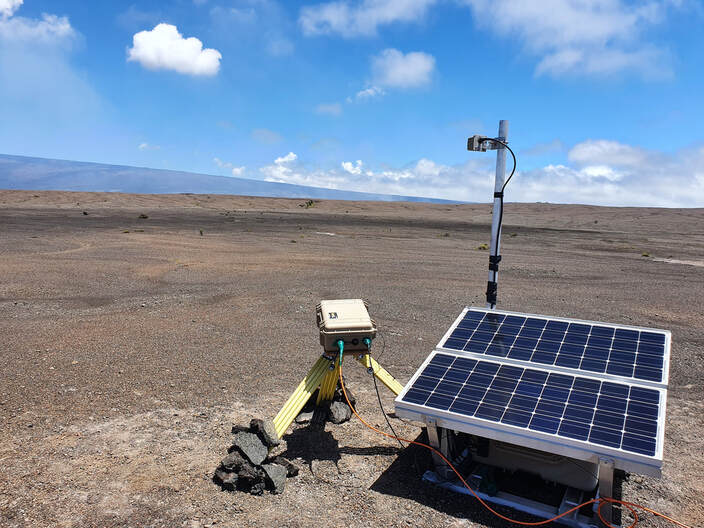

The end of the road...with a lava lake in the distance. The end of the road...with a lava lake in the distance. I should really rename this blog to something a bit more representative of my posts, how about "travelling the world with a UV camera"? The location this time was pretty exciting, the chance to work at Kilauea alongside the USGS (United States Geological Survey) to install one of our UV cameras into the monitoring network. Since 2016 at Sheffield we have been working on our Raspberry Pi UV Cameras. We have now got to the point that these cameras can now be placed out permanently to collect long time series datasets, thanks to the work of Tom Wilkes. Our cameras are now in place, operating remotely in three locations worldwide - Reventador (Ecuador), Lastarria (Chile), and Lascar (Chile). Next up Kilauea, but this represented the next step in our UV camera journey, adding telemetry of data, so that data is collected and (hopefully!) processed in almost real-time. On a personal level, the chance to see one of the most active volcanic sites in the world was also a strong draw. Luckily, some work in another part of the USA meant that my initial arrival into Hilo on the eastern part of Big Island was not steeped in jet lag, stepping off the plane into a wall of moisture and a savaging by three local bugs. Met at the airport by one of the "gas team" at HVO (the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory) it was straight up to the volcano and the offer of a quick tour round some of the fun viewing spots. I had seen some of the time-lapse captures of the collapse of the summit area, but it really was impressive in person, to those who had seen the before and after in person that changes must have been even more dramatic. Of course I was looking forward to seeing the lava lake in person on the first night, luckily the accommodation was right next to a good viewing spot (and for some incredible views of the night sky - were those arms of the milky way spiral I could see?). Braving the wind and somewhat chill air - which felt weird given the abnormally hot weather people were having back home, and here I was in Hawaii - actually cold - out to the viewing spot, which was clouded... A short drive around the crater to the devastation trail and a hike out to a tourist heavy viewing spot and there it was, a nice and calm lava lake doing its slow moving plate-tectonic style thing. My second lava lake (but who is counting...). In the coming days, with access to the restricted area alongside the USGS I would even get to see a close up view at the edge of a road which was no more (see photo above). The next morning work began straight away, albeit with a short detour for a gas mask fit test, a singularly unique experience that is for certain, one I wish I had photos of. Driven down to one of the USGS warehouses a plastic bag was put over my head and interesting scents wafted my way to check I had a sense of smell, add a gas mask and some head shaking to check that the interesting scents were no longer there, and hey presto qualified to wear a gas mask. After this, straight up to the volcano to begin location scouting for the installation. Luckily I had brought one of our mini UV cameras so this process was as smooth as possible. There are a lot of considerations when installing a permanent system - is the spot accessible (for maintenance), does the spot have a good view of the plume that isn't too far away or isn't too close, does the spot have a view of telemetry locations for transmission, and a few other aspects which were a bit surprising - like the presence of the flanks of Mauna Loa in the imagery! Amazingly, the chosen spot was the first visited, logistically it just made sense. Some double checking the next day and the decision was made. The upcoming days were occupied with setting up the new permanent UV cameras for use in the given location, spending time collecting test datasets, installing the camera software in various locations, and writing a detailed guide for use for the specific setup at Kilauea. Over the 12 days on site it wasn't until days 10 and 11 that the installation was finalised and data was coming in regularly. Luckily some good weather on days 7 to 9 helped show us what the cameras could do. Hopefully the cameras will be bringing in data for the foreseeable future! Overall, this trip was a great insight into the workings of a full time volcano observatory and working with the USGS was such an amazing experience in no small part down to the group of dedicated individuals I got the chance to work with. |

Archives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed