|

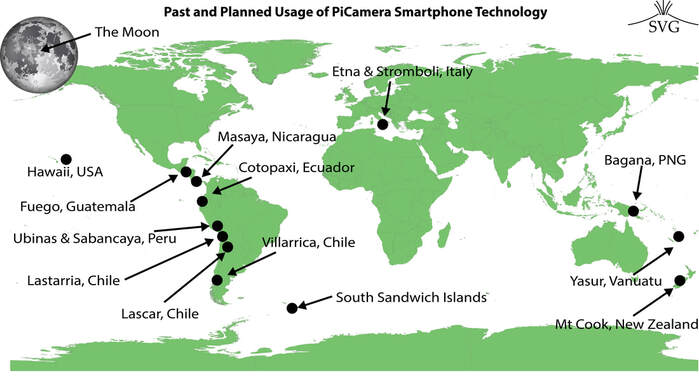

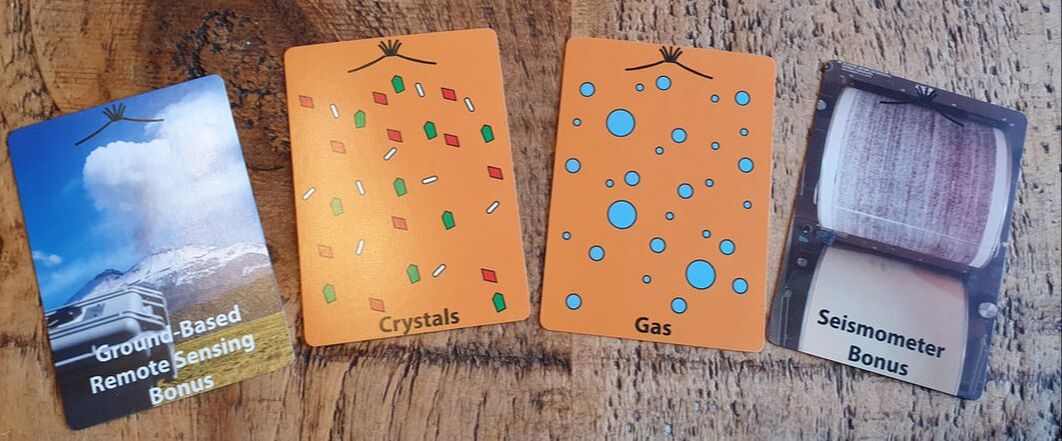

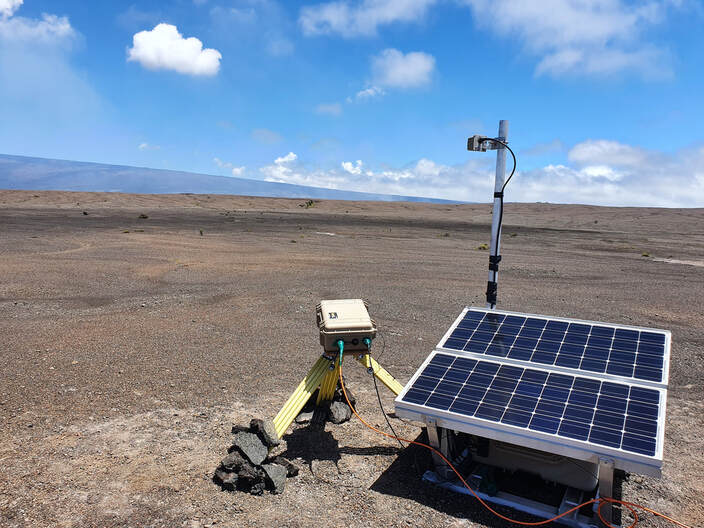

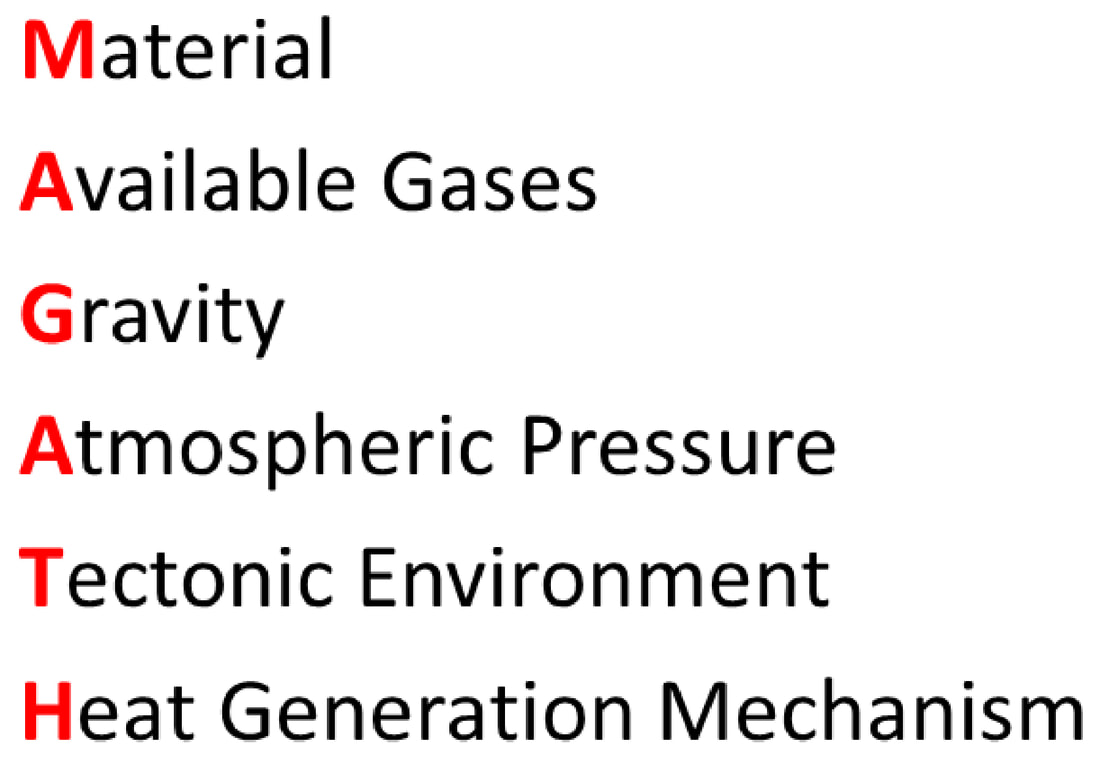

Voltivity is an exciting new card game where players take turns to create volcanic eruptions in a competitive environment and hopefully learn something on the way! The name comes from the genius combination of "Volcanic Activity". Voltivity is turn-based, with players collecting different cards to make different eruptions - termed "volcano recipes" - which involve mixing different magmas, crystals, gas, and also water. For example, want to make a strombolian eruption? Collect some gas and basaltic magma cards. Players can also trade in-between turns adding a bit of communication and a competitive streak to the game. Why did I make the game? I have always enjoyed designing different activities for my modules to depart from the lecture format. In a third year module "Applied Volcanology" I already run virtual reality sessions, have a volcano challenge based assessment (see here), and include a science communication piece. One of the aspects of modules towards the end of the degree I have always wanted to bolster is the refresher of content covered earlier in the course (Week 1 content). Any way to make these parts a bit more fun is a win for me. Hence the idea behind this card game, as a way of refreshing the topic and important terms that will come up a lot during module content, getting the students to think about science communication, but also having a bit of fun in a module. I also get the students to play Volcano Top Trumps with science communication hats on as quick warm up. Comparing and contrasting the two games (Voltivity and Volcano Top Trumps) then provides a lot of potential for discussion.  An example eruption card. An example eruption card. The main aim of Voltivity is to create as many volcanic eruptions as possible, the person with the most points at the end of the game, wins! There is a limit to the number of styles of volcanic activity which can happen per game and the types of magma needed to create these eruptions. This is an attempt to get the students to think about the take home points from the game. For example, the number of volcanic activity styles available for eruption is modelled on real-world volcanic activity frequency. There are lots of lava flows and strombolian eruptions available for people to produce. Likewise there are far more Basalt cards available than Rhyolite. If you want to produce an Ultra-Plinian eruption then there is only one of these available in the game, but it is worth a whole 10 points. This brings a bit of fun strategy to the game. The rarer or more dangerous the eruption - the more points you get - but the more difficult it is to "erupt". Another element to the game are the bonus cards, I won't list them all here, but include cards such as the exsolution bonus, which counts as two gases, and the false alarm bonus, which forces an opponent to remove a volcano of their choosing from an opponent - perhaps that rare Ultra-Plinian event. My favourite part is the "Dante's Peaking" rule, if you can't create a feasible eruption based on the cards you have, then the whole pile of cards goes. So that's a quick look at Voltivity! A big thanks to Tehnuka Ilanko and Thomas Wilkes who helped with an early prototype of the game. Voltivity can be seen in action below.  The end of the road...with a lava lake in the distance. The end of the road...with a lava lake in the distance. I should really rename this blog to something a bit more representative of my posts, how about "travelling the world with a UV camera"? The location this time was pretty exciting, the chance to work at Kilauea alongside the USGS (United States Geological Survey) to install one of our UV cameras into the monitoring network. Since 2016 at Sheffield we have been working on our Raspberry Pi UV Cameras. We have now got to the point that these cameras can now be placed out permanently to collect long time series datasets, thanks to the work of Tom Wilkes. Our cameras are now in place, operating remotely in three locations worldwide - Reventador (Ecuador), Lastarria (Chile), and Lascar (Chile). Next up Kilauea, but this represented the next step in our UV camera journey, adding telemetry of data, so that data is collected and (hopefully!) processed in almost real-time. On a personal level, the chance to see one of the most active volcanic sites in the world was also a strong draw. Luckily, some work in another part of the USA meant that my initial arrival into Hilo on the eastern part of Big Island was not steeped in jet lag, stepping off the plane into a wall of moisture and a savaging by three local bugs. Met at the airport by one of the "gas team" at HVO (the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory) it was straight up to the volcano and the offer of a quick tour round some of the fun viewing spots. I had seen some of the time-lapse captures of the collapse of the summit area, but it really was impressive in person, to those who had seen the before and after in person that changes must have been even more dramatic. Of course I was looking forward to seeing the lava lake in person on the first night, luckily the accommodation was right next to a good viewing spot (and for some incredible views of the night sky - were those arms of the milky way spiral I could see?). Braving the wind and somewhat chill air - which felt weird given the abnormally hot weather people were having back home, and here I was in Hawaii - actually cold - out to the viewing spot, which was clouded... A short drive around the crater to the devastation trail and a hike out to a tourist heavy viewing spot and there it was, a nice and calm lava lake doing its slow moving plate-tectonic style thing. My second lava lake (but who is counting...). In the coming days, with access to the restricted area alongside the USGS I would even get to see a close up view at the edge of a road which was no more (see photo above). The next morning work began straight away, albeit with a short detour for a gas mask fit test, a singularly unique experience that is for certain, one I wish I had photos of. Driven down to one of the USGS warehouses a plastic bag was put over my head and interesting scents wafted my way to check I had a sense of smell, add a gas mask and some head shaking to check that the interesting scents were no longer there, and hey presto qualified to wear a gas mask. After this, straight up to the volcano to begin location scouting for the installation. Luckily I had brought one of our mini UV cameras so this process was as smooth as possible. There are a lot of considerations when installing a permanent system - is the spot accessible (for maintenance), does the spot have a good view of the plume that isn't too far away or isn't too close, does the spot have a view of telemetry locations for transmission, and a few other aspects which were a bit surprising - like the presence of the flanks of Mauna Loa in the imagery! Amazingly, the chosen spot was the first visited, logistically it just made sense. Some double checking the next day and the decision was made. The upcoming days were occupied with setting up the new permanent UV cameras for use in the given location, spending time collecting test datasets, installing the camera software in various locations, and writing a detailed guide for use for the specific setup at Kilauea. Over the 12 days on site it wasn't until days 10 and 11 that the installation was finalised and data was coming in regularly. Luckily some good weather on days 7 to 9 helped show us what the cameras could do. Hopefully the cameras will be bringing in data for the foreseeable future! Overall, this trip was a great insight into the workings of a full time volcano observatory and working with the USGS was such an amazing experience in no small part down to the group of dedicated individuals I got the chance to work with. After 28 months of no fieldwork this trip to Chile couldn't come fast enough. As a volcanologist, for me anyway, there is just something about getting out to a volcano which keeps the excitement for the subject alive. Coupled with a period of study leave the past few months have refreshed and revitalised my drive to continue some of the work I find exciting but also to try a few new things. This was my first trip to Chile and the target volcano Lastarria one of the volcanoes in the Northern area of Chile. From a scientific perspective this trip represents the next level for the work we have been doing in Sheffield on ultraviolet cameras. Tom Wilkes has been working on a permanent system that can simply be left in the field to collect data for periods of months, instead of the shorter field campaigns that I have written about lots before. The group at Universidad Católica del Norte (Antofagasta) have been ardent users of our ultraviolet cameras and are enthusiastic to take this next step with us.  The start of the B885 road, which eventually leads to Lastarria. The start of the B885 road, which eventually leads to Lastarria. The work then we felt was of some importance, however, I am not sure I was fully prepared for how tough the work would be incorporating the altitude and the cold. I have worked at altitude before at Ubinas and Sabancaya in Peru. But on each occasion they were shorter trips and didn't involve overnight stays at significant altitude whilst camping. This journey in Chile started at Antofagasta, sea level, and within a couple hours we reached a place called Agua Verde, which seemed to consist of a petrol station with ice cream and some dilapidated restaurants. A short u-turn and we took a road called the B-885. From the start alongside the gravel road were mining ruins which littered the first few tens of kilometres. We only passed two cars coming in the opposite direction, a road little used it would seem. The landscape was like nothing I had experienced before almost completely lacking in vegetation bar yellowy tufts of grass, with the broad flat plains punctuated by prominent peaks.  The final stretch to Lastarria. The final stretch to Lastarria. The journey along the B-885 took us into the night and after three hours on this road we arrived at our camp. But I wouldn't truly appreciate the landscape we crossed until the return journey. The camp, pictured, was the reclaimed site of previous mining operations. A small corrugated extended shed split into cooking area and a dining area with mattresses for sleeping. That first night of sleep was tough at around 3600 metres and incredibly cold, I don't have an exact number, but needless to say it was cold enough to freeze the water in the plastic bottle at the end of my bed. We spent a total of three nights at the camp and each night felt like an eternity of fidgeting and trying to get comfortable. Sleep must have come at points as I recall dreaming. It is a weird feeling to be physically exhausted and yet not being able to do the one thing that would help. Luckily I found the work during the day to be a distraction from the cold and wind which whipped round the flanks of the volcano.  The fumarole fields. The fumarole fields. In total we went up to Lastarria three times, spending more time on the first two days. Day one was all about measuring the gas release and installing the permanent system at about 4600 metres, next to an old lava flow from the summit area. On day two we went up to 5200 metres and to one of the most prominent fumarole fields I have seen, passing frozen sulphur flows on the way up. Photos just couldn't do the vibrant yellows and oranges surrounding each individual fumarole justice. The other amazing thing about Lastarria is that it's possible to drive right up to the fumarole field along a mazey road, the extent to which mining companies were willing to explore and attempt extraction of resources amongst the furthest and more remote areas is astounding. Day three was a quick pop up to the permanent ultraviolet camera to check operation and then to begin the journey back to Antofagasta. Overall, it was a fantastic experience in the remotest location I have ever been, the cold and camping adding to the experience, somehow enhancing the time spent in the landscape, despite the difficulties sleeping and how tough it felt physically. When it was time to leave it did come as a bit of a relief and my time spent acclimatising to the altitude allowed me to enjoy the landscape as we bounced along past older volcanoes, crossed salt flats and even encountered vicuna running across the road escaping from a wandering fox. As oxygen flooded back on the downward leg sleep took me and then eventually back to Antofagasta. I am certain this won't be the last visit to one of the amazing volcanoes of Chile and I thoroughly look forward to my next adventure. I am always looking for ways to make teaching and assessments more than an essay or exam, but also to try and make these things a bit more world relevant. I may have an unfair advantage here, with a fantastic subject to teach like volcanology! Last academic year I started, alongside colleagues, a new third year module in 'Applied Volcanology'. In this module, we covered three main aspects:

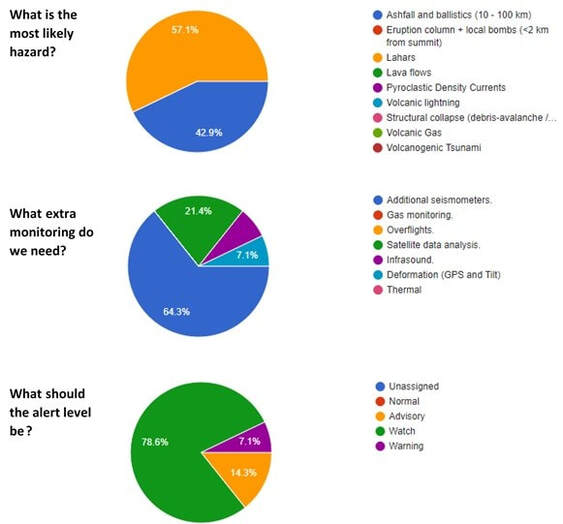

At the beginning of the Volcano Challenge Week (which was actually ten days in the end), the students were thrown into an ongoing, but fictitious, volcanic crisis (at a real volcano). Every two or three days, new monitoring information was released, such as gas composition and amount, seismicity, deformation, and overflight data. From this progressive release of information the students were then asked to write a risk report with an assessment of most likely eruption scenarios, and if possible their probabilities. Given the uniqueness of this assessment, in comparison to those that the students may be used to, they were supported with a specific lecture on hazard assessment and decision making, but also a seminar. In this seminar students were given a short scenario, mimicking the Volcano Challenge week but for a different volcano, and using their expert opinions to gauge what most likely hazards would be, and also think about setting alert levels (see Figure below). Unfortunately, initial plans were for all of this to be in person (scheduled for April/May 2020), however, the content was also quite suited to an online setting using students in breakout groups to discuss the various ongoing and changing fictitious volcanic crisis events.

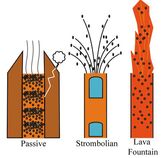

The guardian dogs of Pacaya volcano. The guardian dogs of Pacaya volcano. My third trip to Latin America, and third different country. Following on from Nicaragua and Peru, Guatemala was the destination. This trip was my first for a while, an unfortunate and somewhat stressful serious of last minute events leading up to a summer field campaign to Vanuatu meant that that trip didn't happen. I have thoroughly enjoyed every visit so far to Latin America and Guatemala didn't disappoint. A couple days in Guatemala city to begin with, to reorientate sleeping patterns, prep equipment and bump into fellow volcanologists, then off to San Francisco de Sales on the flanks of Pacaya volcano with colleagues from Sheffield and Liverpool, and our local guide. A quick 45 mins jaunt up the volcano (without equipment this was a breeze!) to take a look at the lay of the land and fly a drone to take a look at the activity of the volcano. The results, a direct view into one of the three vents and a look at the lava flows coming down the flanks. An easy route back down in plenty of time to prep equipment and get an early night's sleep. That first night was an experience. In bed at 9 pm, hoping for a cracking amount of sleep, to be awoken at 12:30 am by a rooster (which sounded like it smoked 80 a day), unusual I thought, can't possibly last long. Oh boy was I wrong. It lasted all night. Then, mercifully, it stopped for 30 minutes. Sleep at last. At 5 am; hoooooonnnnkk, the first 'chicken bus' of the day (the affectionate name for the local colourful repainted US style school buses) announced its arrival, at 5 am. OK, there can't possibly be more, can there? Well at 6 am-ish fire crackers, who knows why, but there they were going off at 6 am. The first nights sleep didn't go well and only improved through the week on use of headphones. It's all well that the first days UV camera fieldwork was a practical no go due to clouds and that napping could happen.  The gas plume on the last day at Pacaya volcano. The gas plume on the last day at Pacaya volcano. On this trip we were performing a combined gas and geophysical (seismic and infrasound) campaign, certainly envied the geophysical setup on the flanks and then that was pretty much it bar changing batteries on the Sheffield lower cost instruments every day. The remaining 5 days of fieldwork were spent plume hunting, we just couldn't get the right angle on the plume (ideally perpendicular to plume travel). An additional issue was that the plume was travelling so quickly that it grounded almost as soon as it was released (the gas travelled directly along the flanks) meaning that we couldn't get a clear view of the plume, and that ideally we needed to get as close as possible or get lucky with the weather. Well, luckily both happened, on Day 2 the plume temporarily lofted from our roadside position and on Day 3/4 we managed to find a good view at Finca El Amate, a local and very hospitable farm discovered by our guide. This also involved a fun truck journey over older lava flows whilst sat in the back, most enjoyable. Day 5 though brought the data home, a change in wind direction and a lofting plume, blue skies, perfect UV camera data. There was a very excitable moment heading out just before 9 am. A casual glance into the sky, hang on a minute, is that plume? That was unusual for our time there! A hasty and rapid ascent with equipment led to 4 hours of great data. Pacaya treating us well on the last day. I also took the time to do a few video blogs whilst out in the field, here is the first, the remainder should follow on: I am always looking for ways of innovating my teaching and attempting to come up with new ideas to communicate the material and ideas to students. So here is one such idea which initially stemmed from some teaching I delivered on planetary volcanology but that I now use across my volcano teaching. The idea is an acronym 'MAGATH' which, when used, (maybe!) helps us to understand volcanic processes throughout the solar system, in terms of how the volcanic activity is generated and the volcanic products or phenomena which may then be produced, along with some of the major controls on volcanic behaviour. So here it is, MAGATH, and what each of the letters stands for:  Example basaltic styles of behaviour, smaller bubbles generating passive degassing and larger bubbles strombolian. Example basaltic styles of behaviour, smaller bubbles generating passive degassing and larger bubbles strombolian. M is for Material. Here we get to the crux of the matter straight away, not all volcanic activity has to be molten rock, indeed, there are several planetary bodies which exhibit ice-based volcanism. Within this we can also have significant variety of rock or type of ice. For example, on the Earth we have basalts, a low-viscosity rock when molten, which commonly exhibits low explosivity styles such as strombolian or lava flows OR we could have a rhyolitic magma which may present in far more explosive Plinian styles of behaviour. There are of course a large number of possible types of material, and nuances to this, but the first step is the understanding that these materials can vary greatly (and themselves have varying properties related to things like silica and crystal content) and can then subsequently effect the volcanic activity type or phenomena which occur. A is for Available Gases. The gases which are contained within magmas are one of the major drivers of explosive volcanic behaviour. Beyond this we can then begin to probe into what types of gas there are, the major constituents on Earth being water, carbon dioxide, and sulphur dioxide, amongst a number of other gases. These gases form bubbles within magmas, it is how these bubbles behave and interact within the conduit which can then lead to the variety of styles of activity that we see at the surface. If we were to take a basaltic magma and add a certain amount of gas to the mix, what style of activity would we see? If we had only enough gas to produce small millimetre sized bubbles we may produce passive degassing, if we were then to grow the size of bubbles in a basalt to metres in length we could generate strombolian activity. G is for Gravity. Have you ever seen the plumes of Io (a moon of Jupiter)? Gravity plays a role in their height and trajectories. How far will a lava flow travel? How high will an eruption column be? Gravity plays a key role in all such questions. Gravity also links very closely with the theme of the next letter A. A is for Atmospheric Pressure. A great example here is to compare the atmospheric pressure of Earth (around 101 kPa) to Venus (around 9300 kPa). Atmospheric pressure will effect the rate of exsolution of gases from a magma, this is the formation of bubbles as a magma rises to the surface. A higher surface pressure means that more bubbles can stay dissolved within the magma, and as gas is one of the major drivers of explosive behaviour this means that we need a higher gas content for magmas on Venus to generate explosive behaviour. Coupled with this, if any activity were to occur, the volcanic products, an eruption column for example, wouldn't reach the same height as on the Earth, this is directly related to the thickness of the atmosphere (which is related to the pressure). Another good example is comparing the trajectory or distance of a volcanic bomb, on the Earth a bomb is subject to a number of forces (air resistance, gravity etc.), at a location such as the Moon where there is little to no atmosphere AND where gravity is lower, a volcanic bomb could travel further. T is for Tectonic Environment. This one is key and is intrinsically linked with Plate Tectonics. Roughly speaking we can attribute certain styles of volcanism to certain tectonic environments (e.g., spreading margin, subduction zone, hot spot), we can then build an expectation of style of activity we may expect, so with a hot spot in an oceanic setting (oceanic crust) we may expect more basaltic style behaviour, such as the Hawaiian island chain, whereas at a subduction zone we may expect more explosive styles of behaviour perhaps related to the production of ashy eruption columns. H is for Heat Generation Mechanism. Volcanism or volcanic activity is, simply put, some form of surface evidence or product of the heating of material (see the link back to the first letter 'M', what material has been heated!). The question is then, what is the mechanism of heating? We can broadly narrow this down to two main mechanisms, the radioactive decay of isotopes and tidal forces. So, MAGATH aims to help students identify: the key factors which act to control style of volcanic activity, how the activity may behave in the atmosphere, and how it is generated. It can then become a framework to build other content around, as needed, and importantly these factors interact. And of course there are many complexities which effect volcanism beyond the examples given here, which are just a flavour. To delve into more I would have to write a book! There are already some great existing volcano books around for more detail and elaboration though. Anyhow, I hope this may be of use, after a quick google the other common use for 'MAGATH' is a German football manager, so all good on that front. I also think it is quite similar to the word 'magma' so could be easier to remember, who knows whether this is actually true or not! As long ago as October 2016 and January 2017 (in academia this really does feel like an age!) I wrote about my ongoing work with colleagues at Sheffield on developing a low cost method for measuring sulphur dioxide release from volcanoes. This work has somewhat 'exploded' since these initial posts, enough that the University of Sheffield media team decided they wanted do a little video feature on it (see below). Here is a little quote from this video by yours truly: Its really exciting to be part of a project which you see from first concept through to finished package.  The travels of the PiCamera. The travels of the PiCamera. That's just it, from an idea, which I seem to recall was hatched in the pub out of necessity, to a working instrument which has now been lent to people for work across the globe and has even been picked up by NASA, all in all, very exciting! During this time we have developed the cameras, from duck-taped monstrosity measuring sulphur dioxide emissions at Drax Power station, through to slightly less duck-taped monstrosity camera at Etna. We finally had a boxed and robust version for work at Masaya, and in recent work we have adapted the cameras to operate from mobile phone batteries and be charged using solar power! We have now got to the exciting stage of distributing and lending our equipment out to collaborators across the globe (see above graphic), which has led to a well travelled PiCamera (our affectionate but functional name for the Raspberry Pi UV Camera) and some exciting developing science. Our work was also recently picked up by the Hackspace magazine which involved an interview with the volcano group here at Sheffield. Overall, it has been a relatively quiet summer on the fieldwork front, but I finally managed to get a paper I had been working on for a while out into the world: "Periodicity in Volcanic Gas plumes: A Review and Analysis", this paper tells the story of the patterns (periodicity) we have detected (up to this point) in measurements of gas release and starts to synthesise the meaning of some of these. This year I have been lucky enough to land some field class teaching time in New Zealand. The trip is an existing course for Level 3 BSc Geography students which visits the South Island. As a volcanologist this was a little daunting given that the active volcanics are on the North Island! Preparation involved a bit more background reading than usually required, but throughout the trip, which involves such a vast diversity of topic areas, from: glaciers in the Southern Alps, fluvial processes, earthquakes and faulting (and more); I discovered how fascinating the landscape of the South Island is. The trip really does cover an amazing suite of geographical phenomena. The one thing it was missing though, some volcanoes... A week before the trip was due to leave, rainfall of epic proportions, landslides and a bridge removal on the west coast meant a change of itinerary, and opened up the opportunity to investigate some volcanology. I am always a bit wary of taking students to look at old volcanics as it can sometimes be a bit difficult to see what is going on, not so with Banks Peninsula! Some fantastic lavas, sediments and debris flows of Lyttelton volcano. I must admit that I am indebted to the PhD thesis of Samuel J. Hampton (University of Canterbury) for the field sites (thesis called: Growth, Structure and Evolution of the Lyttelton Volcanic Complex, Banks Peninsula, New Zealand). Over the week and during preparation I have learnt all sorts about the specifics of the geology and evolution of Zealandia, its great to apply knowledge to different locations. This is something I hope the students get out of the trip too. Coming to New Zealand enables them to see such a range of features within such a short space, really enabling them to use the suite of skills and to test their interpretation of landscapes. In an unrelated observation I may have also had the Howard Shore Lord of the Rings soundtrack mulling round my head. The trip has also been a great opportunity to learn from colleagues who, as far as possible, focus on their specialist fields. I must admit it has been 'cool' learning and visiting the glacial environments, which used to be my favourite topic area during early undergraduate and my A Level days. The response to glaciers to a changing climate in the Southern Alps has been quite eye opening. The chance to see Earth moving processes such as landslides and faulting has been exceedingly interesting as well.

I am currently sat on a glacial moraine, overlooking Mt Sefton, having a thoroughly enjoyable relax, listening to some top tunes and writing this blog post. That's it from me (I'll upload this when I have internet). I have a bit more of this view to enjoy...  A close up of a strombolian explosion at night within the crater at Yasur. A close up of a strombolian explosion at night within the crater at Yasur. Spectacular Yasur just about sums it up. An archipeligo of islands in the Pacific, Vanuatu is home to some of the most unique and interesting volcanoes worldwide, including my target destination, Yasur. I am paticularly interested in a style of volcanic activity termed strombolian, that which is driven by large bubbles that ascend and burst at the surface. A style of activity I have written about lots before. Yasur is unique because of the frequency that these explosions occur and the number of vents at the summit which produce activity. The archetypal Stromboli (see post here), produces activity from 3 or 4 vents every 5 - 10 minutes (ish), this of course varies. Whereas at Yasur explosions were coming from more than 5 vents (it was difficult to tell how many exactly) and occurred more frequently, from seconds aparts to just a few minutes. So, two volcanoes with a potentially similar mechanism for driving the activity but visibly different behaviour at the surface, a perfect reason to study Yasur, all thanks to a Royal Society research grant. The journey to Vanuatu was a lengthy one from the UK, with stopovers in Singapore and Brisbane, before arriving at the capital Port Vila. A few days in Port Vila to acclimatise and sort out officialdom then off on a short internal flight to the island of Tanna. Arriving at Tanna really felt remote, perhaps not as remote as up near Sabancaya, but the tiny concrete airport building and vast lush green forests (I want to call them jungle but not sure I can) were quite something. Picked up in a 4x4 by our lodge owner, its a short 1 hour excursion across a mixture of paved, roads in progress, and dirt tracks. The approach to our 'jungle huts' crossed the ash plane created by the frequent explosions and as we neared the volcano I experienced the familiar buzz of visiting a new volcano.  The volcano Yasur from our tree house vantage point. The volcano Yasur from our tree house vantage point. Arriving at dusk it wasn't possible to take a look at the view, but the next morning after breakfast, up to the treehouse and there it was (see photo on left), the prime measurement spot used for the next few days. The following 7 days were a mixture of hiking around to different spots, heading up to the summit area to observe the activity and make thermal measurements, meeting a wandering pastor, and meeting friendly locals. My favourite moment, returning from a hike up to the summit in the pitch black on a crystal clear night, pausing a moment to take in the prominent Milky Way streaked across the sky with strombolian activity roaring in the background, if only I was a good photographer... It has been a busy year of travel, now some time to write results up. I certainly hope to return to Vanuatu soon!  The top half of the Colca Canyon The top half of the Colca Canyon It has been a mad period of time after getting back from Peru, hence the reason it has taken so long to write this last post! It was a great last few days at the workshop, spending the last couple days listening to some talks and instructing on the use of our Raspberry Pi ultraviolet cameras. One evening we had some telescope time at the hotel we were staying at, pretty cool looking through and seeing the four Galilean moons around Jupiter which was clear enough to see the striping! On our last day in Yanque we had planned to head back up to Sabancaya to get some more data, but alas, the weather Gods were against us, and it still involved a really early wake up time, before 5 am. Plume in the wrong direction and clouds over the summit. Thats the way remote sensing is sometimes! See the video blog below. In all I think we got some decent data from the first day of fieldwork, so not a disaster but its always good to get as much data as possible. A little disappointing but it did mean a visit to Colca Canyon! Quite an impressive area to visit with some condors thrown in too. After this straight back to Arequipa. Heading back down to Arequipa was actually a huge relief on the lungs as far as oxygen content was concerned, but certainly not for all the pollution! A relaxed time for about 24 hours before the trip home, which was a little unorthodox to say the least. Certainly learnt a few things about booking flights for the future, and certainly worth keeping in mind for an upcoming Vanuatu trip, must buy those flights soon. Flights on the way home should have been - Arequipa to Lima to Amsterdam to London Heathrow. So, off to flight number one, at Arequipa discovered a 30 minute delay on our flight to Lima, leaving us an hour to connect to a different flight, this sounded tight to us (me and Tom)...but we were assured this was enough time and were even given row one seats. Pretty sure we sat next to a Peruvian footballer and someone who behaved like a politician. They were personally greeted, this is all the evidence we had, definitely concrete sightings. Landing at Lima, up like a flash, and....we had the joys of the bus journey to the terminal followed by a 10 minute wait to collect bags. Legging it from the domestic terminal to the check-in desks, we were too late. Shuddering to a halt in front of the security cordon we were stopped by a guy with a lanyard who immediately looked at us, stated "KLM - follow me!" and he was off at speed! Assuming that this guy was waiting for us we followed at a matched pace, until some alarm bells started ringing...guy tried to grab my bag to start wheeling it, we were moving away from the terminal, and he even started to get a little agitated when we questioned him about officialdom., pointing at his faded plastic lanyard. A brief return to the terminal showed us that the check-in was closed (in fact we would have struggled to make it if the flight was on time!), we therefore decided to follow, at an increased distance, until it appeared the guy was probably legit and we ended up at airport offices. After an hour of haggling and negotiation we knocked down a 10 day wait for a return flight (mental!), £4000 each for business class the next day, to flights 5 hours later with a lengthy Atlanta layover. Anyhow, we got back, eventually, and that was it for Peru. Overall, an incredible experience and one I hope to repeat very soon. |

Archives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed